This isn’t necessarily any questions or specific thoughts as much as I’m just adding a little to the dialogue.

The EZLN released the Zapatista Women’s Revolutionary Law in conjunction with their 1994 uprising and First Declaration. I think it is interesting to see their declaration in tandem with the reading.

The following are the ten laws that comprised the Women’s Revolutionary Law:

- First, women have the right to participate in the revolutionary struggle in the place and at the level that their capacity and will dictates without any discrimination based on race, creed, color, or political affiliation.

- Second, women have the right to work and to receive a just salary.

- Third, women have the right to decide on the number of children they have and take care of.

- Fourth, women have the right to participate in community affairs and hold leadership positions if they are freely and democratically elected.

- Fifth, women have the right to primary care in terms of their health and nutrition.

- Sixth, women have the right to education.

- Seventh, women have the right to choose who they are with (i.e. choose their romantic/sexual partners) and should not be obligated to marry by force.

- Eighth, no woman should be beaten or physically mistreated by either family members or strangers. Rape and attempted rape should be severely punished.

- Ninth, women can hold leadership positions in the organization and hold military rank in the revolutionary armed forces.

- Ten, women have all the rights and obligations set out by the revolutionary laws and regulations

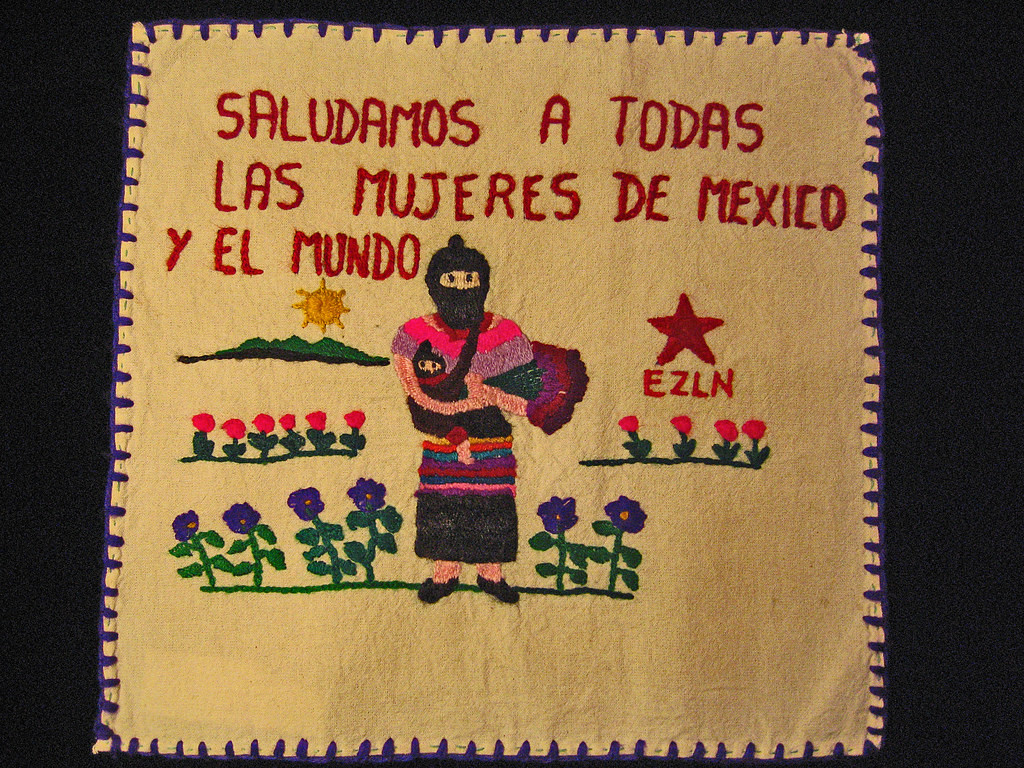

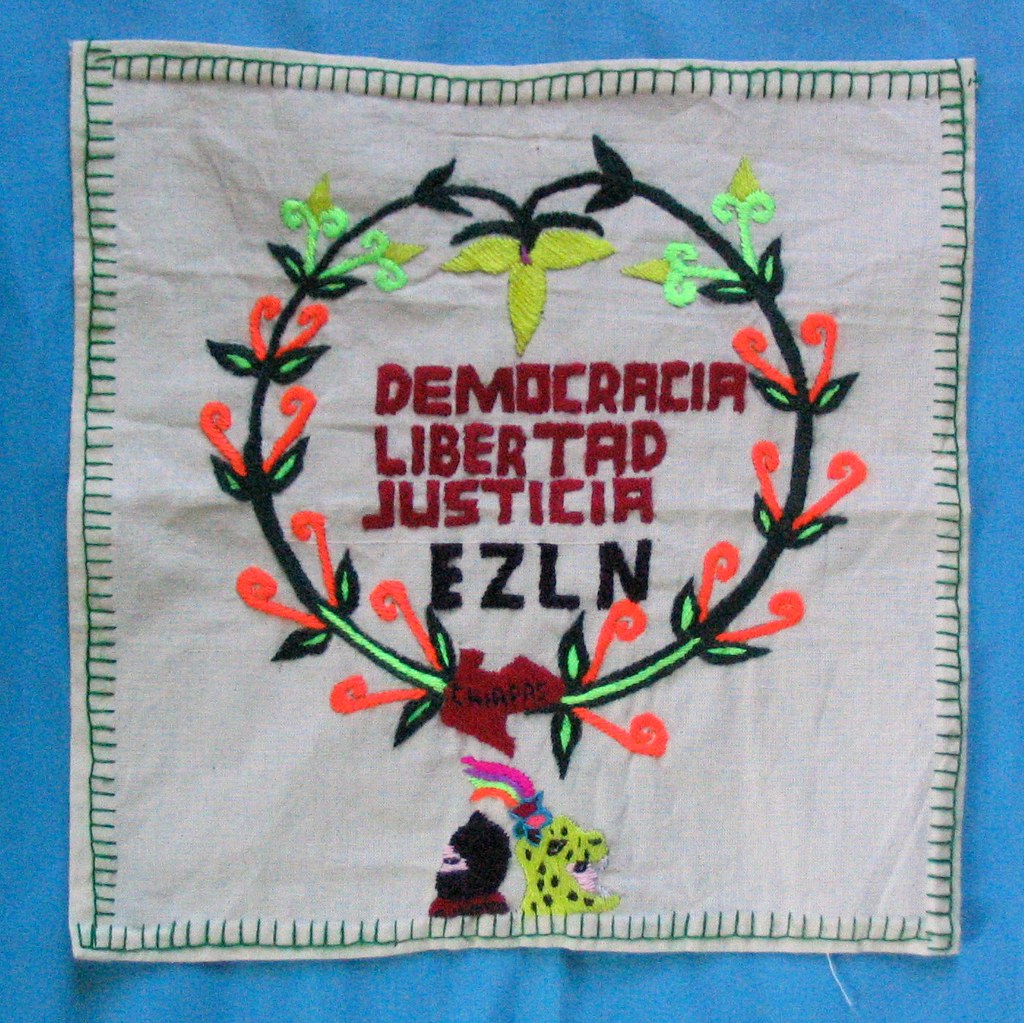

Something else I would like to mention, and I think goes well with the Endnotes, is about women’s labor in EZLN, specifically embroidery. It is a form of capitol, but is also community building and often a form of protest. (I’m taking this from a paper I wrote):

Embroidery is a local trade that women partake in to help subsidize their Zapatista communities and maintain economic independence. The embroideries are sold to tourists throughout Chiapas but can also be bought online. Embroidery is also used as a form of protest and political propaganda. Zapatista women create embroidered flags with political messages to hang throughout their communities. Many of the wears women sell, from bookmarks to bags, have the emblematic Zapatista star, figures wearing the standard Zapatista balaclava, and a myriad of other symbols or sayings related to their political goals. The women gather in cooperatives to support each other’s craftsmanship and ensure fair costs.[1] From the onset the Zapatista movement has been dedicated to the equal rights of women in their communities. Issued in conjunction with the First Declaration by the EZLN, the Women’s Revolutionary Law declared, among other things, a women’s right to partake in the revolution in any way she sees fit, to work and receive fair wages, to bear as many children as she chooses, to education, to be free of violence, and to occupy leadership positions and hold military rank.[2]

In none of my reading on Zapantera Negra (the exhibition that my paper was about) did I find specifics about the embroidery collectives who completed the work, only that there were two, one focused on hand embroidery and the other machine embroidery. More generalized information about Zapatista embroidery collectives is available. The collectives are not formed only to produce embroideries. They are gendered spaces where women provide support to one another and discuss both the personal and the political. Anthropologist Mariana More spoke with one collective member, Auralia, who was 16 at the time. She stated,

“In our collectives, we work the vegetable gardens, we have rabbits, we learn to do embroidery and make artisanry. But not only that, it is only the beginning. There we also give talks and reflect on our life in the house. Those who are older explained to us who are younger how we need to defend our rights. Autonomy is against the bad government and also against the men who don’t treat women well.”[3]

Mora rightfully points out that the collectives blend the economic, political, and personal, blurring the line between the public and the private, between politics and life itself.[4] She goes further, stating that from material work emerged a “process of collective self-reflection,” that provides a space for thinking through the micro-politics of everyday life, generating new forms of knowledge to address local inequalities.[5] Fascinating in their own right, I hope only to have established that embroidery collectives are gendered spaces where women cooperate to produce works that have the potential to reflect upon and project their political goals.

[1] Sirena Pellarolo, “Zapatista Women: A Revolutionary Process Within a Revolution,” (keynote address for the International Women’s Day event organized by the California State University, Los Angeles, California, March 8, 2006), accessed March 20, 2017, http://www.inmotionmagazine.com/auto/sp_zw.html.

[2] EZLN, “Zapatista Women’s Revolutionary Law,” El Despertador Mexicano, January 1, 1994.

[3] Mariana Mora, “Decolonizing Politics: Zapatista Indigenous Autonomy in an Era of Neoliberal Governance and Low Intensity Warfare” (PhD diss., University of Texas at Austin, 2008), 186.

[4] Ibid., 186.

[5] Ibid., 187.

Random examples:

Finally, and I know this is so long! After reading Endnotes I thought of artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles. She is a feminist artist whose work is service oriented and conceptually explores domestic, civic, and service maintenance.

She coined the term “maintenance art.” She does maintenance work as a performance but also, after writing her manifesto, she spent four days logging her actions (or labor) as housewife, mother, and artist.

I think that’s it!